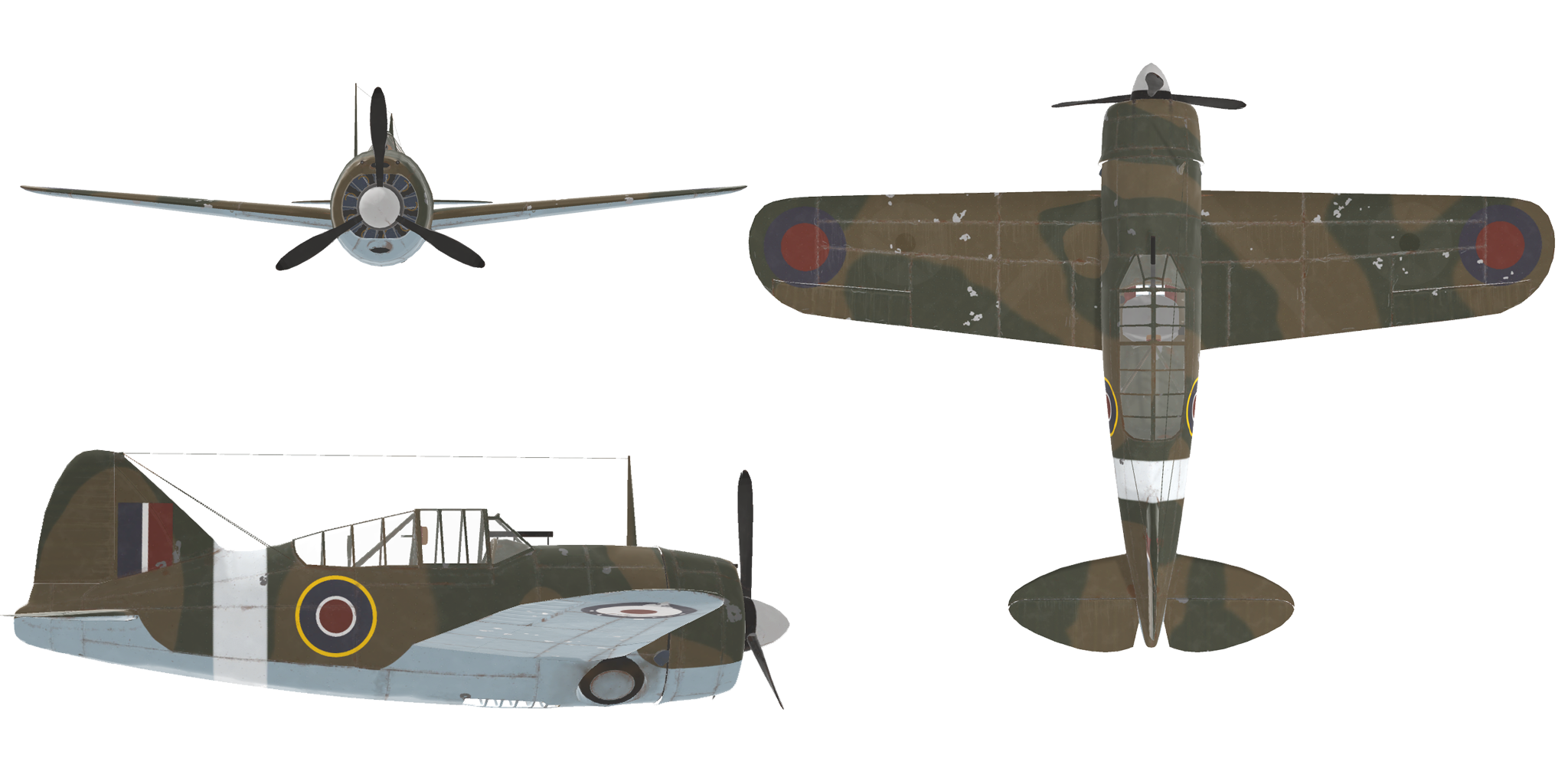

BUFFALO MK. I (F2A)

The F2A Buffalo was already on its way out by the time the United States entered World War 2, the planes considered overweight and too cumbersome to fly. But the RAF considered them good enough for their pilots, ordering 170 of the 339Es to bolster their efforts in the tropical Far East.

The British China-Burma-India 339Es were known as the Buffalo Mk I. A number of changes were made to the original F2A design to bring the aircraft specs in line with European standards. Armor plating was installed for the pilot and armored glass in the windscreen, and the original propeller was replaced with a 10-foot Hamilton Standard propeller. However, these changes increased the weight to 6500 pounds (2950 kilograms). Its rate of climb was only 2600 feet (790 meters) per minute and its top speed reduced to 330 miles (530 kmh) an hour.

The Buffalo formed the basis for five Commonwealth squadrons, namely the 67 and 243 Squadrons of the RAF, the 21 and 43 Squadrons of the RAAF, and the 488 Squadron of the RNZAF.

Each squadron was issued 15 airplanes. Four were stationed in Singapore while the 67th Squadron was based in Burma. A lack of trained pilots meant surplus Buffalos had to be put into storage. The inexperience of some Far East RAF pilots was put on stark display when a whopping 20 Buffalos were lost in training accidents during the autumn of 1941.

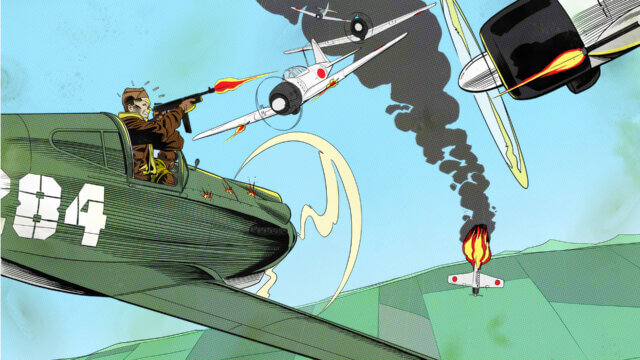

Once the RAF pilots had adapted to the Buffalo, they managed to hold their own against the IJAAF’s Ki-27s and Ki-43s in the China-Burma-India theatre particularly Burma, Malaya and Singapore. It was only when the Japanese Navy A6M Reisen (Zero) came into play that the Buffalo’s shortcomings became visible for all to see. The Zero was more agile and more heavily armed and ran rings around the sluggish Buffalo in dogfights. The RAF tried to correct this by shedding as much weight as possible. They used lighter guns and lessened the fuel load, but it made no real difference to performance. A number of Dutch pilots finally decided to halve both their fuel load and the amount of ammunition in the wing, but even then, the Buffalo was not able to match the performance of the superior Japanese fighter.

The 67 Squadron flew alongside the Flying Tigers on multiple sorties, such as in defense of Rangoon in Burma during the Japanese Christmas raids of 1941. However, the lack of spare parts slowly picked apart the squadron’s strength, and only six Buffalos were left operational when Rangoon fell to the Japanese in the spring of 1942.

The situation grew worse as the Japanese gained territory, forcing Commonwealth squadrons to withdraw to Singapore Island. By February of 1942 there were only a few airworthy Buffalos left. These were pulled back to the islands of the Netherlands East Indies and at least four were turned over to Dutch squadrons when the British were evacuated.

Although the Buffalo is seen by some as a failure, many Buffalo-strengthened units fought strongly until the sheer number of Japanese fighters overwhelmed them. Official numbers are impossible to verify, but around seventy Buffalos were lost in combat, forty were destroyed on the ground, up to forty were lost in training and non-combat accidents, six were sent to India, and four were sent to the Dutch. In the final tally, the RAF Buffalo squadrons of the CBI racked up 80 combat kills.